Here is what I am reading today:

“In an article published online June 3rd by the journal Nature, a team of electrical engineers and neuroscientists working at Stanford University propose a new theory of the brain activity behind arm movements. Their theory is a significant departure from existing understanding and helps to explain, in relatively simple and elegant terms, some of the more perplexing aspects of the activity of neurons in motor cortex.

In their paper, electrical engineering Associate Professor Krishna Shenoy and post-doctoral researchers Mark Churchland, now a professor at Columbia, and John Cunningham of Cambridge University, now a professor at Washington University in Saint Louis, have shown that the brain activity controlling arm movement does not encode external spatial information—such as direction, distance and speed—but is instead rhythmic in nature.”

“”I think there’s enough evidence to say that musical experience, musical exposure, musical training, all of those things change your brain,” says Dr. Charles Limb, associate professor of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins University. “It allows you to think in a way that you used to not think, and it also trains a lot of other cognitive facilities that have nothing to do with music.””

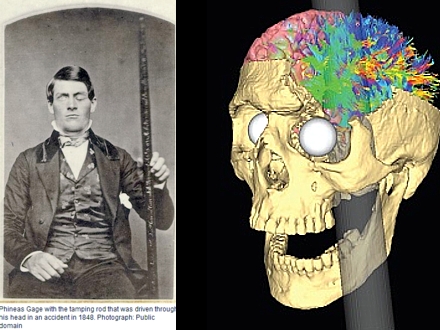

“Anyone who has studied psychology or neuroscience will be familiar with the incredible case of Phineas Gage, the railroad worker who had a metre-long iron rod propelled straight through his head at high speed in an explosion. Gage famously survived this horrific accident, but underwent dramatic personality changes afterwards.

In recent years researchers reconstructed his skull and the passage of the rod through it, to try to understand how these changes were related to his brain damage. Now, neuroscientists from the University of California, Los Angeles have produced Gage’s connectome – a detailed wiring diagram of his brain, showing how its long-range connections were altered by the injury. “

“It’s well established that exercise substantially changes the human brain, affecting both thinking and emotions. But a sophisticated, multifaceted new study suggests that the effects may be more nuanced than many scientists previously believed. Whether you gain all of the potential cognitive and mood benefits from exercise may depend on when and how often you work out, as well as on the genetic makeup of your brain.”

3 Comments

klovelace · June 4, 2012 at 2:45 pm

I read the article “Music and the Brain” and thought the findings discussed were extremely interesting. As a psychology major and music minor, I enjoy reading about how our brains react to beats and melodies. The part describing “earworms” had some interesting points, and I would like to see more research in this area and what makes a person more likely to experience these music “loops” more than others. The examples given from studies about other species and music were fascinating, and this is an area I would be very interested in studying. Who knew that monkeys couldn’t tap their feet along to a beat, but some birds can dance to certain tunes?

LauraPolacci · June 6, 2012 at 8:27 am

I was particularly interested in reading the article about exercise and memory, as I run on a regular basis and do not pride myself on having the best memory. It was interesting to hear that those in the study who exercised regularly for a month AND exercised the morning before taking the memory test did improve their scores, while this affect wasn’t seen with those who hadn’t exercised the day of the test. Personally, I know I run to clear my head, so perhaps this would have an affect on boosting my memory after running. I also thought it was very interesting that 30% of people with Caucasian heritage produce the BDNF gene that “blunts” BNDF production after exercise, meaning even by exercising on a regular basis, their memories would not improve. I hadn’t heard of this gene before, so now I’m interesting to research more about it and see if the gene that “blunts” it’s production can be counteracted by something, something other than exercise that is.

LauraPolacci · June 6, 2012 at 8:38 am

I choose to read the article about music and the brain, partly to see what brain changes I was missing out because I am not a musician. I was pleasantly surprised to find out that playing music or composing music isn’t the only way to change one’s brain involving music, but even musical exposure (ie. listening to music) can change one’s brain. This is great news for me, as I appreciate listening to music, but have no other musical inclinations or abilities. It’s also interesting to hear some of the preliminary thoughts and research about “ear worms” and how they play on a loop over and over again, because I currently have a few songs that are stuck in my head that I’d love to forget! I also thought it is interesting that music may have evolutionary adaptations, as I had previously learned otherwise in former classes. If that is the case, then it would make sense why people are attracted to musicians, and this would not be a useless adaptation!

Comments are closed.